The most destructive earthquake in the southeastern U.S. occurred here

On this day in 1886– at about ten minutes shy of 10 p.m., a massive earthquake shook Charleston. It resulted in the deaths of 60-100 people, caused millions of dollars in damages, and was so powerful that people as far away as Boston could feel it. And at any moment, it could happen again.

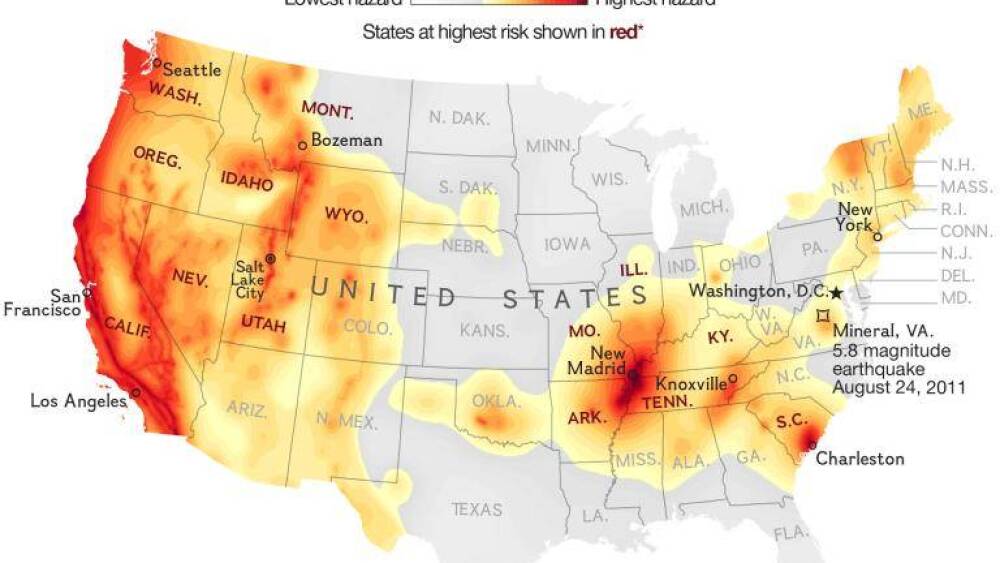

Earthquake hazards within 50 years show Charleston is at the highest risk of anywhere on the East Coast | U.S. Geological Survey

South Carolina is among 16 states (the only one the East Coast) facing the highest risk for earthquakes. And while we’ve only experienced one other earthquake close to that magnitude (Union County in 1913), scientists now predict another damaging quake, potentially of such scale, within the next 50 years.

Concerned yet? Read on to learn more about what could happen to Charleston the next time the ground beneath us starts to give way.

Quick science lesson:

Two types of earthquakes exist: interplate + intraplate. 90% of the world’s seismic energy is attributed to interplate earthquakes, which occur along the edges of where two tectonic plates meet. Plates are constantly moving against one another, building stress– and the accumulated stress is what results in an earthquake.

The second, rarer type of earthquake occurs within a single plate. The 1886 earthquake– along with every quake occuring in our region– is a categorized as an intraplate earthquake because we’re not located along a plate margin. Scientists haven’t yet figured out what causes these types of quakes.

The 1886 earthquake

On that fateful night exactly 132 years ago, the most powerful + damaging earthquake in the southeastern United States to date befell near Summerville, in an area of seismic activity we now call the Middleton Place-Summerville Seismic Zone. Seismographs weren’t around yet, but modern experts estimate it carried a magnitude of 7.3.

The initial shock lasted one minute and was catastrophic. Charleston was destroyed. Its epicenter was in Summerville, but damage was reported hundreds of miles away– as far as Alabama, Kentucky + Ohio.

Charleston was already strained. The Civil War had just ended two decades prior. King Street was just hitting its stride, and its businesses were in the process of installing glass storefronts. St. Michael’s Church had just finished repairing its steeple, which had been damaged by a hurricane the year before.

An estimated 7/8ths of Charleston’s buildings were condemned by the quake. Brick + stone structures incurred the most damage. Other buildings were cracked, but not destroyed. Many of those– like the Dock Street Theatre and Charleston City Hall– were repaired, this time with added reinforcements like earthquake bolts and iron rods.

What we know about the next one

In 2014, the U.S. Geological Survey updated its hazard maps, placing Charleston at a higher risk for a significant event than previously indicated. A study commissioned by the South Carolina Emergency Management Division concluded a similar quake today could result in 45,000 lives lost, hundreds of thousands of people displaced, and, to the tri-county alone, damages reaching $10 billion.

Aftershocks could cause bridges to collapse, the loss of access to power + water for the (surviving) homes in the area, and the ignition of hundreds of fires. It would take months just to restore utilities to working conditions.

Silver lining: being that we are located along the Atlantic coastline, + because most of our active faults (the aforementioned one in Summerville included) are located on land, it’s unlikely a quake could result in a tsunami (most of those happen in the Pacific). There’s still a slight risk of one happening here– but if one were to occur, we’d at least have some warning beforehand.

How to prepare

If you’re indoors + feel an earthquake, it’s best to get under a sturdy object (such as a desk), hold on to its legs, and duck your head between your knees. If outside, try to lie down until the shaking stops. If possible– avoid laying near power lines, buildings, + trees.

As for protecting your property, earthquake insurance is an option. After the USGS upped S.C.’s risk for a quake, some insurance carriers (State Farm, Liberty Mutual + Farm Bureau) upped the rates for earthquake coverage (which is separate from home insurance). Still, less than 10% of South Carolinians carry any type of earthquake insurance. Should you buy it? Just like any other type of insurance, it boils down to whether you’d prefer to play it safe + pay up front, or bet against the odds of this happening again in your lifetime.

For more preparation tips, check out SCEMD’s earthquake guide.

//

A catastrophic earthquake like the one Charleston experienced in 1886 could happen again at any moment. Maybe the ground will have already begun to shake as you began reading this story... or, maybe, we’ll all be long gone when the next disaster hits. We just don’t know.

So, should you be scared? Consider this: August is ending, which means September– a.k.a. the time in which hurricane season is most active– is upon us. And October– when the creepy clown epidemic tends to flare back up– is right around the corner.

In other words, there are threats lurking around every corner. And while it never hurts to be prepared, nothing useful will come from living in fear.

– Jen